This is my first book, published in October 2020 by Crowood Press. This page is not an electronic copy of the book that you can read for free; if you want the book, you'll have to buy it. Rather, it contains some details of why and how the book was written, various things that I didn't have space to put in the book or were too detailed for the expected reader, and - regrettably - errata.

Because I was asked to.

One day in early 2019 I received an email from Alison Brown at Crowood Press, saying she'd seen my website and asking if I'd be interested in writing a history of the Bakerloo Line. Before replying, I did a bit of due diligence to check it appeared genuine (it did) and asked my wife for her opinion (she was very much in favour).

So I wrote back to say I was interested. And everything snowballed from there.

I had read Charlie Stross's "Common Misconceptions About Publishing" , so I understood that things weren't always going to go my way. As it was, things weren't too painful.

Alison sent me a form to fill in. Even though the book was their idea, I had to put together a description and a list of chapters with a couple of sentences describing each of them. Originally we had agreed 40,000-50,000 words and about 200 photos, but the acceptance was conditional on changing this to 50,000-60,000 words and about 100 photos. Since I was more worried about finding photos than writing words, I was happy to agree to that. (In the end, the delivered manuscript was 63,450 words, including captions, and proposed 121 photos and diagrams. These numbers have changed slightly during the production process.)

So we signed a contract on 11th April and a cheque arrived for a first advance on the royalties. I'd estimated how long it would take and doubled it (there's an old computer programmer's rule of thumb: estimate how long the task will take, double it, then go up a unit, so if you estimate 3 weeks, quote 6 months) so the contract had a deadline of 31st October.

Now to actually write the thing.

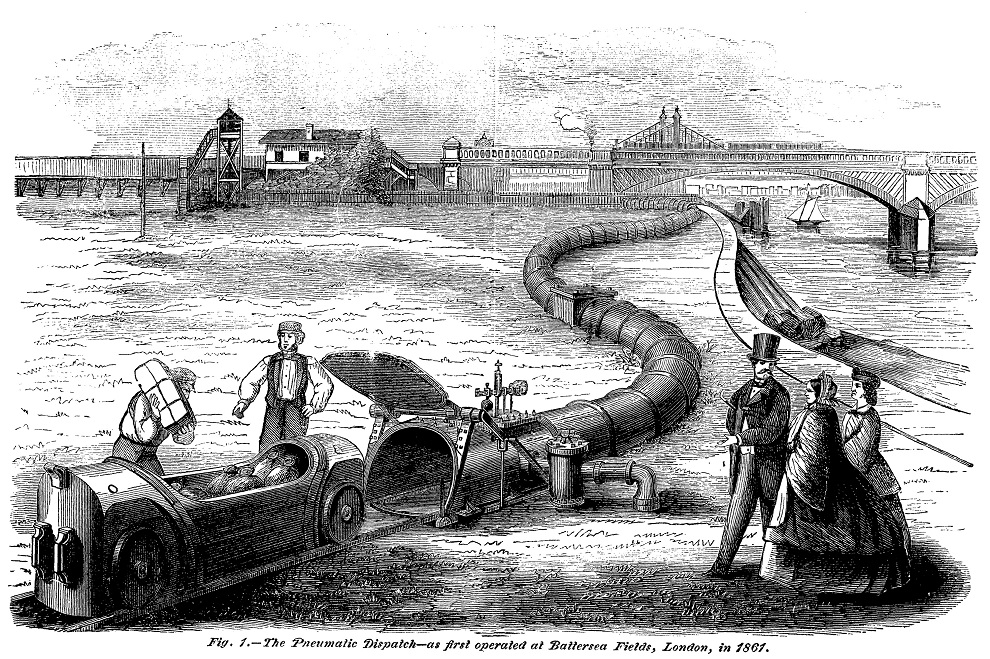

Most of the next three months were spent doing research. I thought I knew the basic history - pneumatic tubes, Baker Street & Waterloo Railway, fraud trial, Yerkes, Watford extension, Stanmore takeover, Jubilee Line, Lewisham proposal, that sort of thing - but as I researched further I found a range of details I hadn't realized, from Whitaker Wright's underwater conservatory, through two long books of lightly fictionalized records of Yerkes's dodgy activities, to how often someone wanted to extend the Bakerloo to Camberwell. I ended up with a long list of notes with references to sources, sorted roughly by date. But when I came to do the writing I regretted having not put a lot more detail into those notes; all too often I had to go back to the source to see what on earth I was thinking of when I wrote the note. Lesson learned for next time.

Okay, it's early August. Half my time's gone and I haven't written a word! Better sit down and start.

Microsoft Word isn't my favourite editor, but it's what the publisher wanted and it will suffice for the job. However, what if I mess something up or my laptop crashes? No problem: I'm a programmer and I use source control systems, notably Git. So I create a Git repository on my laptop and clone it to my Unix server. From then on, every day I commit all my files (not just the manuscript) to the repository and push it across to the server. I can now get back any previous draft and it's all available if the worst happens and the laptop disc is wrecked. A few times I also cloned the repository to a memory stick and left that in the office, just in case the house caught fire. I've also got cloud backups.

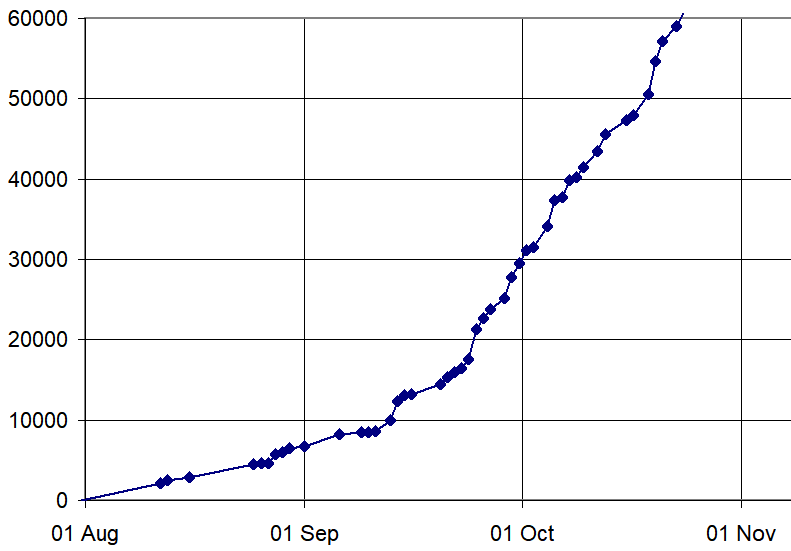

Sometime in late August, Linda asks me how I'm progressing. I check the word count and it's only about about 6000 words - 10% to 12% of my target with a third of my writing time gone! This isn't Writer's Block, it's just me not putting in enough effort. I go back through the Git repository and note down word counts for every day that I'd done some writing, put them into an Excel spreadsheet, and told it to draw a graph. Hmm, I'm going to be finished somewhere around the start of May, and that isn't without any tidying up, revision, or dealing with family emergencies. Linda tells me that I'm suspending any other projects I'm working on and doing nothing in the evenings except writing.

From then on the curve takes an upwards trend:

In the end I did 46 significant writing days, averaging 1318 words a day; the daily counts varied between 10 and 4183 (low numbers were because the time was spent rewriting material or digging through research again).

By early October I could see that I was running out of time to finish. For the last three weeks I'd been averaging about 1,350 words a day but, even though that rate predicted a finish in two more weeks, I knew there would also be proof-reading and sorting photos to be done. So I wrote to Alison warning her that I might be a couple of weeks late and apologizing profusely. Her response was reassuring:

two weeks after the deadline is not even classed as late! We have books that are 3 years+ late!As it was, the first draft was finished on 24th October but it was early on 21st November when I finally emailed everything to her. (The delay was partly things like re-reading, making changes, and sorting out photos, but there were also some external events that took up several days.)

Photos just required a lot of choosing and sometimes a bit of cropping (plus use of ImageMagick for harder stuff like the montage of tiles on page 83), but diagrams meant real work. In most cases I had a mental image of what I wanted, but that didn't make it easy, and I'm not a good (or even mediocre) artist. Thankfully I was used to markup languages, XML, and in particular SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics). For those not aware of it, SVG is a form of XML for constructing diagrams in the way that HTML is used for web pages. A big advantage was that I could take data out of tables I already had and very quickly turn it into a diagram. For example, the Stanmore part of the diagram on page 157 has source code looking like this:

<g transform="translate(0,-10)"> <path stroke="#FFAA00" stroke-width="0.08" fill="none" d="M 67 8 H 64" /> <path stroke="#FFAA00" stroke-width="0.08" fill="none" d="M 64 6 H 62" /> <path stroke="#FFAA00" stroke-width="0.08" fill="none" d="M 64 4 H 47" /> <path stroke="#FFAA00" stroke-width="0.08" fill="none" d="M 49 2 H 45" /> <path stroke="#8080FF" stroke-width="0.08" fill="none" d="M 48 0 H 45" /> <g transform="translate(-0.3,0.3)"> <g transform="translate(64.62,8.50) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Stanmore </text></g> <g transform="translate(63.27,7.01) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Canons Park </text></g> <g transform="translate(61.56,5.12) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Queensbury </text></g> <g transform="translate(60.23,4.30) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Kingsbury </text></g> <g transform="translate(57.38,4.10) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Wembley Park </text></g> <g transform="translate(55.09,3.80) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Neasden </text></g> <g transform="translate(54.24,3.94) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Dollis Hill </text></g> <g transform="translate(53.03,5.60) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Willesden Green </text></g> <g transform="translate(51.84,5.22) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Kilburn </text></g> <g transform="translate(50.75,5.60) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">West Hampstead </text></g> <g transform="translate(50.14,5.20) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Finchley Road </text></g> <g transform="translate(49.53,5.70) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">Swiss Cottage </text></g> <g transform="translate(48.61,4.90) scale(0.04,0.04)"><text font-size="16" transform="rotate(90)" text-anchor="start">St. John's Wood </text></g> </g> <path stroke="grey" stroke-width="0.05" fill="none" d=" M 64.62 7.68 V 8.5 M 63.27 7.01 V 6.5 M 61.56 5.12 V 4.8 M 60.23 3.83 V 4.3 M 57.38 3.67 V 4.1 M 55.09 3.22 V 3.8 M 54.24 3.94 V 3.7 M 53.03 5.03 V 5.6 M 51.84 5.22 V 4.5 M 50.75 5.05 V 5.6 M 50.14 4.87 V 5.2 M 49.53 4.01 V 5.7 M 48.61 3.12 V 4.9 M 46.55 0.51 V 2.7 V 7 " /> <path stroke="green" stroke-width="0.1" fill="none" d=" M 64.62 8.5 L 63.27 6.5 L 61.56 4.8 L 60.23 4.3 L 57.38 4.1 L 55.09 3.8 L 54.24 3.7 L 53.03 5.6 L 51.84 4.5 L 50.75 5.6 L 50.14 5.2 L 49.53 5.7 L 48.61 4.9 L 46.55 2.7 " /> <path stroke="brown" stroke-width="0.1" fill="none" d=" M 64.62 7.68 L 63.27 7.01 L 61.56 5.12 L 60.23 3.83 L 57.38 3.67 L 55.09 3.22 L 54.24 3.94 L 53.03 5.03 L 51.84 5.22 L 50.75 5.05 L 50.14 4.87 L 49.53 4.01 L 48.61 3.12 L 46.55 0.83 M 49.53 4.01 L 48.61 3.17 L 46.55 0.51 " /> </g>Those interested in the topic can work out all the details for themselves. But the important point is that the columns of numbers beginning "64.62" are the "Ongar" values (see pages 154 and 155) for the stations while the other numbers are things like the station and ground heights or depths, so I just had to copy the existing information and then put the correct wrappers around it. So once I've written those wrappers (of which there are very little), ImageMagick (again) will convert it to an image in fractions of a second. If I don't like something, such as the font size for the names, it's trivial to fix.

Right at the beginning of December I was tidying up a image rights issue when I came across the photo that is now on page 123. Given this was the only colour photo of the blue stripe that I'd ever come across, I really really wanted to include it but the manuscript was already in the typesetting and page layout stages (which I had no control over). I sent a begging email to Alison to ask if I could add it in. She said yes, but only gave me 24 hours and said that this was absolutely definitely the last change of this scale. Colour-rail were kind enough to do me a high-resolution scan within a few hours of me asking, so I just managed to get it included, but only just!

My original proposal said "A History of the Bakerloo Line". The contract reduced this to "History of the Bakerloo Line". Somewhere in the production process it became very definitely "The History of the Bakerloo Line". I hope my predecessors won't feel insulted; it wasn't my choice.

The index didn't have to be ready at the same time as the manuscript, but I knew I'd have to produce one. I'd been offered to have the index done professionally, but only if I paid for it. Even if I did accept the offer, I'd still have to check it out, which meant I'd have to do the work myself to check it. So, do it myself.

I decided that I wasn't going to do this by hand. I also wasn't going to wait until the rest of the text and pagination had been agreed and then have to do it in a rush. This was going to be done with the power of the computer. I cut and paste the manuscript into a text file and removed things like images. All the captions and feature boxes, which were the things most likely to get moved around, went to the end of the file. I then found a few characters not used anywhere (not very hard) and decided those would be markers for index entries and other notes (e.g. "X, see Y" or page numbers). I then started reading the text and marking potential index entries as I came across them (a single-word entry was marked with a plus, so "+Waterloo", while multi-word entries went in braces, so "{Baker Street}").

On the way, I discovered a problem. On 12th January I wrote an email:

In chapter 3 I've written "White" twice when it should be "Wright". One is just after image 15; the other is at the start of the sidebar titled "Whitaker Wright".How embarrassing! The technical editor clearly read my email, because the problem had been fixed in the first proof.

Having marked up a file, I wrote a set of scripts that took the file, extracted the index entries, did some transformations (e.g. "Escalator" and "escalators" were changed to "escalator"), then produced the index. Initially everything was on page 0, because I hadn't put any page markers in, but I did test the script could handle them, of course. The captions and "feature boxes" were kept separately in the index source file so that if they moved page I only needed to change one page marker.

The first version of the index had about 1200 entries. On reporting this, I got back:1200 entries is an awful lot! Previous books in this series have had between 200 and 600 the better indexes tending toward the upper end of that range.Oops. Okay, time to do some thinning. After a lot of work, I got it down to 823 entries occurring in 3965 places. I also suggested places where main and sub-entries could be combined; e.g.

District Line 36, 47, 67, 101, 106, 111-112, 120, 132, 156could be reduced to:

electrification 29, 37-38, 46, 52

Embankment station 45, 52, 96

relationship with Metropolitan 22, 77

trains 115, 128

District Line 36, 47, 67, 101, 106, 111-112, 120, 132, 156 (electrification) 29, 37-38, 46, 52 (Embankment station) 45, 52, 96 (relationship with Metropolitan) 22, 77 (trains) 115, 128which would save 94 entries (though not necessarily that many lines).

The actual index in the book has 686 entries. To obtain this, the 42 "X: see Y" lines were removed and 95 subordinate entries have been lost by combining (see here for both sets of missing material). Unfortunately, my suggesting for combining entries wasn't followed; instead, the lists of numbers were just combined. While duplicates were eliminated, no attempt was made to create or merge ranges, so we have ended up with:

District Line 22, 29, 36, 37-38, 45, 46, 47, 52, 67, 77, 96, 101, 106, 111-112, 115, 120, 128, 132, 156instead of:

District Line 22, 29, 36-38, 45-47, 52, 67, 77, 96, 101, 106, 111-112, 115, 120, 128, 132, 156

It also turned out that the appendices had been rearranged to make the index fit in. This meant that references to page 156 were all wrong (most are to 155; a couple to 154).

One other thing I'd done was to give names in their natural form, though still sorted by surname. As it said at the top, names are given in full at the correct position for the surname, so "Frank Boyd May" occurs after "Marylebone". However, this was clearly unacceptable to someone, because all such entries were changed back to the "May, Frank Boyd" form. Three cases clearly weren't thought through when doing this, because you will find

John, Elton 68among the Js and

R.M.S. Oceanic 33half way through the Rs.

R.M.S. Titanic 33

On 4th February I got an email saying they were going to rearrange the book from my planned 19 chapters to 13 (these exclude the introduction and the three appendices). Four pairs of adjacent chapters would be combined while near the end three more would be merged into one. New titles were proposed both for these and for some others, some of which I didn't like. I enquired as to the reason, which basically came down to the sizes being too uneven. I therefore came back with the present arrangement, which they accepted. For those interested, here's what happened:

| Before the Bakerloo | left unchanged | |

| Iron and Clay | merged into Building the Bakerloo; the boundary is at the heading Planning the Bakerloo | |

| Building the Bakerloo | part 1 | |

| part 2 | became The Wright Stuff | |

| Saved by Yerkes | left unchanged | |

| Opening | merged into The Bakerloo Opens; the boundary is at the heading The Early Years | |

| The Early Years | ||

| Call My Bluff | merged into Extending the Line; the boundary is at the heading Watford | |

| Watford | ||

| Improvements | left unchanged | |

| Stanmore | left unchanged | |

| World War 2 | name adjusted to World War II | |

| 50s 60s and 70s | name adjusted to 1950s, 60s and 70s | |

| The Jubilee Line | merged into Jubilee and Beyond; the boundary is at the heading Politics | |

| Recent Events | ||

| Trains | left unchanged | |

| Signalling | left unchanged | |

| Safety | merged into Safety and Danger; the original chapter titles are still headings | |

| Danger | ||

| Future Plans | left unchanged | |

The changes weren't much work; usually just a bit of stitching at the join. The biggest one was the split of "Building the Bakerloo", where a fair amount of material had to be moved from after the boundary to before it to fit the split of themes. I didn't really feel that "Iron and Clay" fit in with the next part, but admittedly it was very short. But as soon as I thought of "The Wright Stuff", I was converted!

I had asked the technical editor to send me proofs in electronic form as it would make it easier for me to do the proofing. We agreed he would send a PDF and I would send an FDF back with the corrections; we did a test run on a small document to check this would work. In fact, in mid-February a large bundle of paper arrived. Instead of starting to work on that with a red or green pen, I emailed asking for the PDF; it arrived with an apology: "we're not used to authors who don't use quill pens".

I had to convert the PDF to plain text, which involved some issues with the two columns being the wrong way round or entire lines being treated as one string. But nothing some scripting shouldn't solve. I could then run a diff against the original manuscript and examine the discrepencies.

The first proof had a total of 437 corrections! While I don't intend to list them all, they included:

In late March there were three queries from an independent proof-checker, all of which were easy to resolve. Then in early April a PDF for "Proof v3" arrived (no, I don't know what happened to v2). This time the FDF only had 65 changes. Most of these were things from the first proofing that hadn't been fixed: to my annoyance, the spurious precisions were still there while, to my horror, so was the major chapter boundary problem. This time, as well as emailing back the FDF, I had a chat with the technical editor about both of these (he said it was the typesetters doing it).

On 30th April v4 arrived, with corrections already marked up. I made a further five: two misplaced commas, two missing spaces, and a query about some wording. I had to reply quickly as the publisher was going into furlough for all of May.

The lockdown meant that related organizations, like the printers, were also closed, slowing the whole process down.

And then all was quiet for months. Until in late September I got an email from the marketing manager followed, a couple of days later, by the first copy of the book!

The publisher's policy is that cover images and the frontispiece are copies of images elsewhere in the book. This is why there is no specific caption provided for them. Specifically, the front cover photos are found on pages 116 (upper) and 107 (lower, but see the next paragraph), the back cover photos are found on pages 130, 50, and 111 from top to bottom, and the frontispiece is repeated on page 71.

In fact, it is obvious that the lower picture on the front cover isn't the same as the one on page 107. I have no idea why the publisher chose to do that but don't care enough to find out. Both pictures were taken from roughly the same place on the northbound platform at Waterloo, facing south, a couple of minutes apart. The train in the cover picture was heading to Queen's Park.

A number of photos were taken from the LURS photo collection or provided by other people as shown in the captions. I am grateful to everyone concerned for this.

The photos on pages 6-8, 11, 18, 21-32, 42-50, 52, 53, 56, 57, 62-64, 68, 71, 73, 74, 83-89, 95, 96, 102-104, 105 (lower), 107, 110, 111 (upper), 112-114, 130, 133 (lower), 138, 141 (upper), 148, and 155 were all taken by myself and I hold the copyright in them.

The figures on pages 37, 76, 80, 82, 102, 131, 137, 149, and 157 were drawn by myself from various sources; again, the figures themselves are copyright.

I have good reason to believe that the photos on pages 12, 39, and 90-93 are out of copyright. I would be pleased to add credits here and in future editions of the book if anyone can advise me.

The photo on page 40 is not subject to copyright.

Notes on individual photos can be found in the next section.

Near the end of the first column, "this is, were unable to pay money they owed" should read "that is, were unable to pay money they owed".

Half way down the second column, "the only places where the line runs under private houses" should read "the only places where the original line runs under private houses".

Near the top of the second column, "100 ft/sec (30 m/s)" should read "100 ft/min (30 m/min)".

Near the end of the main text, "Elephant" should of course read "Elephant & Castle".

Near the top of the second column, "four-car shed" should read "four track shed".

The name "Mary Ashfield Eleanor" should read "Marie Ashfield Eleanor".

Half way down the second column, "Honeypot Lane was too long" should read "Honeypot Lane ran past all three stations".

In the second column, "six stations just outside it" should read "eight stations just outside it".

Half way down the first column, "the technology used and separate peak and off-peak fares were introduced" should read "the technology used; separate peak and off-peak fares were also introduced".

Near the end of the first column, "one or four junior gatemen" should read "one, two or four junior gatemen". Also see the notes for page 47.

Shortly before the heading in the first column, "Two were removed following service reductions in November 1981 and eighteen went over the next two years should read "One was removed following service reductions in November 1981, four more the next year, and fifteen were replaced over the next two years".

Near the end of the second column, "heavy rain had cause excessive pressure" should read "heavy rain had caused excessive pressure".

In the last line of table 5, "Acadia Road" should read "Acacia Road".

The "Ongar" value for Watford Junction should be 74.22.

Bakerloo station names in the tables in the appendices are not referenced in the index. This was a deliberate decision but the note saying so has been removed.

Harrow-on-the-Hill should refer to page 151, not 150.

kilometre posts should refer to page 154, not 156.

Ongar system should refer to page 154, not 156.

Paddington should also refer to page 56.

Queen's Park should also refer to page 99.

All other references to page 156 should be to 155 instead.

The following entries were placed in "J" and "R" rather than the planned "E", "O", and "T":

Elton John 68

R.M.S. Oceanic 33

R.M.S. Titanic 33

That photo was supposed to go at the end of the book, with the caption beginning "The end.". Unfortunately, the publisher disagreed.

The driver of that train saw me taking photographs at the north end of Harrow & Wealdstone station and offered me a cab ride into the siding and back again. I was very tempted but, regrettably, had my daughter with me and didn't feel it was reasonable either to ask to bring her as well or to leave her unattended on the station. So, regrettably, I had to decline. (My daughter appears in one of the photos in the book, but I'm not saying which one.)

Though the acknowlegements just say "Crowood", I originally named Alison Brown, the commissioning editor who first got in touch with me, worked me through the steps of becoming an author, and answered my odd questions. Since then, Robert Zeally, editorial manager, took me through the copy-editing and proofing stages to end up with the finished book. His assistant Alex Carter also helped out with this.

Although there wasn't room here, I'd like to acknowledge the historians of the Underground who have come before me, particularly T.C. Barker, Desmond Croome, John Day, Mike Horne, Alan Jackson, Charles Lee, Michael Robbins, and Douglas Rose. I can only aspire to meet the standards they have set. In particular I'd like to remember Mike Horne, who died on 2020-03-26 (not related to the Covid-19 pandemic). His website can be found here. I met Mike once when, if I recall correctly, he invited me to listen to him give a talk one evening after which we - and others - went to the pub. He made use of the information on this web site and provided me with useful information and comments in return.

We caught the 142 because it was a red bus and so could be used with a "Twin Rover" (see also page 109). Back then, London Transport buses were divided into red ones in roughly what is now Greater London and green ones ("London Country") further out; Watford was well into the outer zone. Red buses were numbered 1 to 299, green buses 300-399 (north of the Thames) and 400-499 (south of the Thames). The 142 was one of the two red buses that went beyond the boundary between red and green to Watford; it ran from Kilburn Park station via Edgware and Stanmore to Watford Junction. The other was the 158 (now 258) from Rayners Lane (now South Harrow). There was also the 292A from Borehamwood via Edgware and Stanmore, but that only ran on Saturdays and even then not in the evening. (My thanks to Yumpu for some of this information.)

The photo was taken at Elephant & Castle station.

The Via Trinobantina ran from Calleva Atrebatum (near modern Silchester), via Pontibus (somewhere in the Virginia Water to Staines area) and London, to Caesaromagus (Moulsham, in Chelmsford) and Camulodunum (Colchester). The part east of London would have roughly followed the original route of the A12.

The quote is from an item in The Times called "Omnibus Law", on page 3, column 5 of issue 16013.

Charles Pearson was mostly out of scope for this book, but details of his proposals are available on the Internet.

Picture from Illustrated London News courtesy of Joe Brennan. The railway running across the river is the LB&SCR line to Victoria station; the building at left is the original Battersea Park station. Behind the railway can be seen the Chelsea Suspension Bridge.

At this time the curve in Great Scotland Yard marked the end of a cul de sac perhaps 70 metres long, running alongside a wharf serving an inlet from the Thames, which was somewhat wider then. The Waterloo & Whitehall would have run along this before crossing the river. On the other side, College Street ran along the north edge of Jubilee Gardens to Belvedere Road, after which Vine Street ran in a straight line to the edge of Waterloo station.

I've been unable to understand why some sources claim the Waterloo & Whitehall would have been 1200 metres long: that distance would either require a huge diversion or would put the Waterloo terminus east of the main station, in Lower Marsh.

Scientific American (15:368:1866) claims there were four sections of pipe, not five. However, the underwater distance would have been about 430 metres while the sections were 67 metres long. Even with a sloping tunnel down to the end pipes, that would still need five sections.

A chain is a unit of length in the Imperial system. It was the standard length of a surveyor's chain and is 22 yards (20.1168 metres), so there are 80 chains in a mile. 2 miles 13.8 chains is therefore 3496 metres.

The Alpine orogeny is responsible for most of the major mountain ranges in Europe, north Africa, and south-western Asia, including the Atlas, Pyrenees, Alps, Apennines, Balkans, Caucasus, Hindu Kush, and Himalayas. It was caused by Africa and India pushing north into Eurasia. England was outside the direct action of the Alpine orogeny, but the forces pushing up the Pyrenees also caused a bulge known as the Weald-Artois Anticline, stretching from Winchester to Lille; in England the edges of the anticline now form the North and South Downs. The ground north of that then folded inwards to form the London Basin with the Chilterns north of that.

The "Inner Circle" is now known as the Circle Line, though the latter now includes an extension to Hammersmith. The term "Inner" was used because the Underground used to have Inner Circle, Middle Circle, Outer Circle, and Super Outer Circle routes, though only the first was actually a complete circuit.

The "mismatched addition" was added in 1960; see page 82 for more about the station.

Tunnel diameter is an important factor in the cost of building a tube line. Most of the expenses of tunnelling are either proportional to the circumference (e.g. the cost of the iron tube) or to the cross-sectional area (e.g. the cost of removing spoil from the tunnel). The costs for the BS&WR were therefore 14% and 30% greater than the C&SLR with its smaller tunnels, while the London County Council's proposals would have been 38% and 90% more expensive than the committee's.

The Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway extension mentioned went ahead; the company renamed itself the Great Central Railway as a result.

Witley Park has stories of its own. For example, allegedly Wright didn't like the location of a hill on the estate and promptly ordered it to be moved that day. Wright's mansion burned down in 1952 but has since been replaced. The underwater conservatory is not open to the public.

The School for the Indigent Blind was founded in 1799 based on one in Paris. The original proposed site was on the other side of St. George's Road but that was in use by the Bethlehem Hospital ("Bedlam") and could not be obtained (the hospital site became free in 1930 and was turned into a park while the building became the Imperial War Museum in 1936). After the sale of its site to the BS&WR the school moved to Leatherhead.

Preference shares in companies are quite common but, for those readers who haven't come across them, they basically trade off a higher probability of dividends for a lower dividend. Dividends are paid out to the preference share holders, but only up to the amount named, before going to the other share holders. There can be several classes of preference share.

For example, suppose a company has shares with a nominal value of £100 each in three classes:

| Total | Class A | Class B | Class C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 0.50 | - | - |

| 100 | 1.00 | - | - |

| 200 | 1.00 | 0.50 | - |

| 450 | 1.00 | 1.75 | - |

| 700 | 1.00 | 3.00 | - |

| 770 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 0.10 |

| 1050 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 0.50 |

| 1400 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 |

| 2800 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| 4900 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 6.00 |

| 5950 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.50 |

Most railway lines in the UK, but not the London Underground, use the terms "Up" and "Down" to describe the two directions along a line. This probably derives either from canal practice or from early lines running downhill from coal mines to rivers or ports. Today, the "Up" direction is normally towards the principal terminus of the railway line and the "Down" direction is away from it. Most of the main lines out of London are therefore "Up" towards the London terminus and "Down" away from it; thus it is "Down" from King's Cross to Newcastle-upon-Tyne and from Victoria to Brighton.

(Originally the Great Central Railway from Marylebone northwards via Finchley Road and Wembley Central was "Down" towards Marylebone because it was an extension of the Manchester, Sheffield, & Lincolnshire Railway and so its main termini were in these areas. At some point the direction was reversed, so it is now "Up" to Marylebone.)

Lines that go across the major routes tend to vary and may change direction. The North London Line is "Down" from Camden Road to meet the lines out of Euston and from Camden Road via Gospel Oak and Willesden Junction to Richmond, but is also "Down" in the opposite direction from Camden Road to Stratford and from Gospel Oak to Barking and Tilbury.

The early Underground lines used these terms, with the Metropolitan Railway being "Up" towards Aldgate and "Down" towards the various country termini, while the Metropolitan District Railway was "Up" towards the various western termini and "Down" towards Whitechapel. As a result, a clockwise "Inner Circle" train would be "Up" throughout its journey.

While the terms used to be in general public use, these days they are limited to railway operators and enthusiasts.

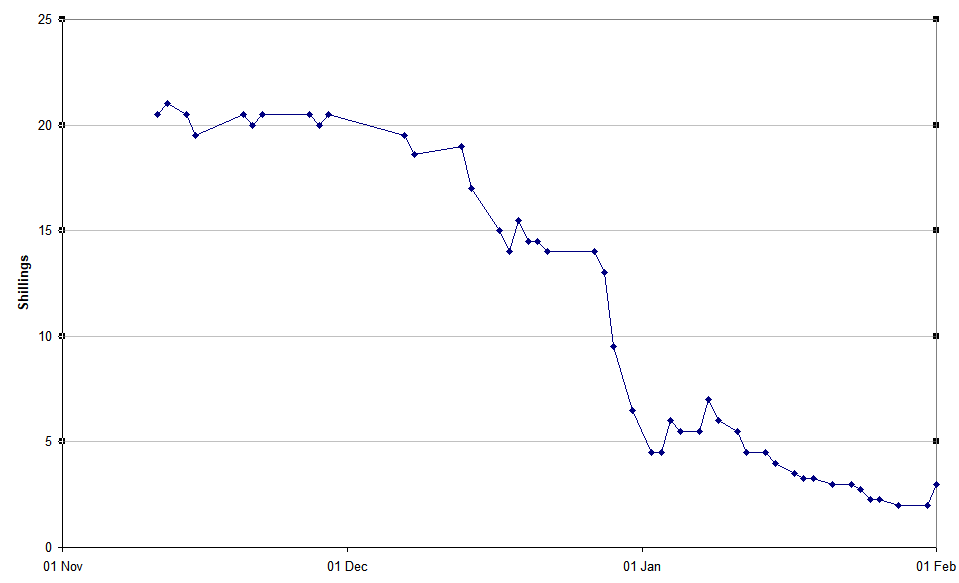

Here are the London & Globe share prices during the relevant period. Not all prices were published; I suspect that they were only reported when they changed.

20 shillings was the face value of the shares.

SS La Lorraine was built at St.Nazaire in 1899 and operated by the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique of France. She was launched on 1899-09-20 and started her maiden voyage on 1900-08-11, from Le Havre to New York. From 1914 to 1917 she was used as an armed merchant cruiser, the SS Lorraine II. Her last voyage, again from Le Havre to New York and back, started in 1922-10-01 and she was scrapped at St.Nazaire at the end of the year.

The US Supreme Court case is Wright v Henkel, 190 US 40.

RMS Oceanic was the second transatlantic ocean liner of that name operated by the White Star Line, best known as operators of RMS Titanic. Like most of WSL's ships, Oceanic was built by Harland and Wolff in Belfast. She was launched on 1899-01-14 and started her maiden voyage, from Liverpool to New York, on 1899-09-06, at which point she was the largest ship in the world, a title she kept until 1901. At the start of World War I the Oceanic was converted to an armed merchant cruiser and on 1914-08-08 she was taken into Royal Navy service. As HMS Oceanic, she was assigned to patrol the area between Scotland and the Faroe Islands. Following a navigation error during the night, on the clear and flat calm morning of 1914-09-08, Oceanic ran aground on the Shaalds of Foula (a well-known danger to shipping in the Shetland Islands). Though there were no casualties and the entire ship's company was taken off without difficulty, the ship itself was completely wrecked. The last person to leave the ship was its First Officer, Charles Lightoller, who had the dubious privilege of being the most senior offier to survive the sinking of the Titanic.

The original "straphangers" statement was actually made at an annual general meeting of one of Yerkes's companies (recorded by a reporter who had bought a single share so he could attend) and was "The short hauls and the poeple who hang on the straps are the ones we make our money out of" ("haul" being the journey made by a passenger).

Another Cowperwood story involves one of the river tunnels. Cowperwood needed a piece of ground to dig a new tunnel portal but the owner refused to sell the ground and the seven-storey building on it for less than about three times what Cowperwood was willing to pay. One Saturday evening, after the close of business, 300 labourers turned up and started to excavate; by sundown the next day the building had been demolished and the tunnel was well under way. When the owner tried to get an injunction to stop the work, Cowperwood's company sued him for interfering with the tramway's business. Cowperwood then kept the matter in court for several years until the owner was willing to settle out of court for a more reasonable price.

The original Piccadilly Line ran from Finsbury Park to Hammersmith with a branch from Holborn to Aldwych. The Great Northern & Strand Railway became the section from Finsbury Park to Holborn and Aldwych, while the Brompton & Piccadilly Circus Railway became the section from Piccadilly Circus to South Kensington. Finally, a proposal to build an express tube line under the Metropolitan District Railway turned into the section from South Kensington to Barons Court Holborn to Piccadilly Circus was added to join the separate companies and, at the western end, the line extended to Hammersmith on the surface next to the MDR (the tracks were later rearranged to put the Piccadilly inside the District, where it remains today).

The express tube line would have descended from the surface between Earl's Court and Gloucester Road and terminated about 21.5 metres below Mansion House station. There would have been one intermediate station at Embankment, 19 metres below the existing District platforms and so passing well under the Bakerloo.

Lots Road sits on the north side of Chelsea Creek and so the photograph is taken facing north. It became operational in February 1905 and had a generating power of 50 MW. It burned around 700 tonnes of coal a day until converted to heavy fuel oil in the 1960s and then natural gas in the 1970s, before being finally shut down on 2002-10-21; eventually it was converted into apartments in 2017-8. It is not obvious from the picture, but this side is the boiler hall; there is a lower turbine hall on the other side. The "elephant trunk" held a conveyor that took coal up to roof level and then along to bunkers occupying much of the top quarter of the building, from where it was fed into the tops of the boilers. It was probably removed soon after Lots Road was converted to burn oil in 1963; two of the chimneys were reduced to roof level and capped around the same time.

Oxford Circus, like several other stations, had been designed to lower standards than the Yerkes group wanted; for example, the station tunnels were shorter than on the other two Yerkes lines. When the UERL decided to rearrange the foot tunnels to be more user-friendly, the Board of Trade (who had to approve the changes) insisted on higher standards of access and safety, requiring the rebuild.

When Yerkes returned to New York he stayed in the Waldorf-Astoria hotel as his estranged wife refused to let him into their house. He died there at about 14:20 on 1905-12-29 and was interred in a mausoleum in the Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn, on New Year's Day. His estate was initially thought to be $22 million but much turned out to be covered by debts or consisting of dubious stocks and bonds. He actually left only $200,000 to his wife, though she had use of one-third of the estate during her life, but he also funded a hospital for the poor she had been requesting for 15 years. However, it was never built, the estate having mostly vanished in debts and legal fees. The only legacies to survive are the observatory (see next page) and the transport systems he developed.

The large crater at upper left with the smaller one above it is Pierce; the smaller one is Swift (previously Pierce B). Benjamin Pierce (1809-1880) was an American mathematician and Lewis Swift (1820-1913) an American astronomer. The pair at the top are Cleomedes F (left) and FA (right); Cleomedes itself is the huge crater to the north, named after a Greek astronomer of the first century BCE. The filled-in crater to their right is Eimmart C with FA and F just above it; Eimmart itself is the deep crater on the edge of the flat area (Mare Anguis) at top right; Georg Eimmart (1638-1705) was a German artist-astronomer who founded an observatory in Nuremburg castle. The crater to the right of Yerkes is Picard, the largest on the Mare. while the filled in one below and between them is Lick, with the much deeper Greaves (previously Lick D) touching it at the top. Jean-Felix Picard (1620-1682) was a French astronomer who was the first to measure the size of the earth (to within 0.44%), while Lick is named after James Lick (1796-1876), a carpenter who became the wealthiest man in California and whose estate funded an observatory, this one just east of San Jose, California. William Greaves (1897-1955) was a British astronomer.

26 km/h is the scheduled speed today in the tunnel section, but that includes all stops. The average speed over the entire run between Elephant & Castle and Harrow & Wealdstone is 30 km/h on the same basis.

The Outer Circle forms the boundary of Regent's Park, though on the north side greenery and the London Zoo extend across the Regent's Canal to Prince Albert Road. There is also a road in the park called the Inner Circle, which is actually a circle about 325 metres in diameter. See the notes for page 22 for the Underground's Outer Circle.

H.G.Follenfant suggests that a depot needs about 200 square yards (167 square metres) of land for each car it maintains. London Road depot is about 12,000 square metres (1.2 hectares or about 3 acres) and so, by that rule, can handle around 70 to 75 cars.

See page 116 for detailed descriptions of the original trains.

A six-car train would have a driver at the front in his cab and a conductor on the platform at the rear of the first car, then gatemen on the platforms at the rears of the second, third, fourth, and fifth cars. The last car would be a motor car with a driving cab at the rear and so no platform needing a member of staff.

A three-car train would have a driver at the front, either in the cab of a motor car or on the platform of a control trailer. The conductor would be at the rear of the same car. A gateman would be at the rear of the second car and another would be needed at the rear of the third car if it was a motor car. The second gateman was not needed if the train had the control trailer at the front; it's not clear what he did when the train was going that way, or if the rear platform was placed out of use in some way when the motor car was at the front so that only three staff were needed.

In 1907 "headway clocks" were added to the departure ends of the platforms at Trafalgar Square. These were clocks which started ticking from zero as a train departed and could display up to 12 minutes; drivers and guards were supposed to use them to keep the trains running evenly. Next to them were illuminated indicators which could show "EARLY" or "LATE" as appropriate. The indicators disappeared by the early 1960s and the clocks themselves probably were removed as part of resignalling in the 1980s.

Starting from September 1909, many station lifts - including most of those on the Bakerloo - were fitted with bells rung electrically by an approaching train; this would tell the liftman to bring the lift down to platform level.

Information about the Ringways scheme is available at the Pathetic Motorways site and, in more detail, at roads.org.uk.

Car 238 was one of the two 1914 Stock trailer cars (see page 117 and the notes for that page). After withdrawal it went to the Isle of Wight to become a bungalow.

The picture was taken from the footbridge at the south end of Derby Road, which long predates the present A411 road bridge next to it. Except that the trees have grown, the view from the bridge now is much the same as then, something that isn't true for most of Watford.

The North West London Railway's intermediate stations were:

In their 1906 Bill the NWLR proposed having four connections to the surface, using 1 in 15 (6.7%) gradients. The purpose wasn't clear: were they for tram-trains running on to the surface, or were they simply intermediate termini in popular areas? The four were:

The proposal to join to the Bakerloo also replaced the Maida Vale station by two new ones, at St.John's Wood Road and Abercorn Road.

Boxmoor is now a suburb of Hemel Hempstead and the station was renamed accordingly in stages between 1912 (when it became "Boxmoor and Hemel Hempstead") and 1963 (when it lost the second part of "Hemel Hempstead and Boxmoor").

The picture was taken on 1928-03-17 by Ken Nunn, from north of South Kenton station. The bridge in the far distance carries the Metropolitan Railway and the LNER (formerly GCR) across the LMSR (as it was then). At the time the bridge only carried four tracks; it was rebuilt when the line was widened to 6 tracks in 1932. The footbridge connects Conway Gardens to a footpath to Northwick Park hospital, though at the time the park and hospital site was a golf course while the other side was open country. This bridge has also been rebuilt since the photo was taken. The building in the distance is apparently an electricity generation or distribution site. To the right of the train it is just possible to see a path across the fields to the embankment carrying the Metropolitan and, beyond that, new houses on Draycott Avenue.

More precisely, the divergence between the Euston and Broad Street routes of the New Lines is within the tunnels roughly 50 metres east of the eastern portals of the mainline tunnels. Each of the four tracks then rises to meet the main lines separately, ensuring that all moves are non-conflicting.

For those without a diagram to hand, the higher-numbered platforms at Paddington are those on the northeast side.

The train is mostly 1938 Stock, but the second car is a '58' trailer - see page 121. The signal box is Watford No.1, which controlled the main lines south of the station (including the signals at that end of the station). There were four boxes in total: No.2 controlled the main lines north of the station, No.3 the three St.Albans branch platforms and access to the adjacent carriage shed and sidings, while No.4 controlled the New Lines. Signal WF29 (controlled by No.4 lever 29) is just visible at the right.

Watford Junction power signal box opened on 1964-07-05, replacing No.1 and No.2 boxes. No.3 closed on 1973-11-25 and No.4 on 1967-01-08, the power box taking over the relevant areas. It closed on 2014-12-29. (Closure dates are the last day in service.)

Platform 5 was originally about twice as long as the other "New Lines" platforms and connected to the main line at the far end. It was sometimes used to park one train while other trains worked in and out of the London end. In November 1963 a footbridge was built across the gap between platforms 4 and 5 to provide direct access to platform 6 (for main-line trains to the north) rather than requiring passengers to go down one flight of stairs and then back up another; the track north of that was lifted. In January 1967 the platform 5 track was lifted entirely.

"Oerlikons" were the LNWR "Oerlikon stock" built by the Metropolitan Carriage Wagon & Finance Co. Ltd at Saltley between 1915 and 1923, for use on the LNWR New Lines and Richmond to Broad Street services. They were named after the source of their electrical equipment: Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon of Oerlikon, Switzerland. There were 75 sets of three cars (3rd class motor, composite trailer, 3rd class control trailer), though normally operated in pairs with the motor cars at the outside ends, plus 3 spare motor cars. They were withdrawn between 1955 and 1960. Motor car 28249 (originally 31E) is preserved at the National Railway Museum in York.

The initial 1915 build was 38 sets, numbered 05 to 42, plus five extra motor cars. A second build in 1921 was another 30 sets, numbered 43 to 72, plus another three motor cars. Finally, in 1923 the LMSR ordered 2 motors, 7 trailers, and 7 control trailers. Sets 01 to 04 were the 1914 "Siemens stock"; very similar to the Oerlikons but with different electrical equipment.

In set ##, the motor car was numbered ##E (so 01E to 72E), the trailer 3##E, and the control trailer 6##E. The extra motor cars from the 1915 build were originally 43E to 47E, but in 1921 they were renumbered 251E, 250E, 253E, 252E, and 255E in that order, with the three new ones being 254E, 256E, and 257E. The LNWR kept the sets together and normally in pairs with adjacent numbers (e.g. sets 15 and 16 stayed together); the even-numbered one was at the Euston/Broad Street end and the odd-numbered one at the Watford/Richmond end. The spare motor cars were only used when one of the service ones was being overhauled, after which the original was returned to its set.

In 1923 the LMSR renumbered all of the cars in a new scheme; the changes are too complicated to list here. The LMSR also stopped keeping motor cars with their trailers, though the trailers mostly stayed in their original pairs until the 1930s.

The Oerlikons were replaced by new class 501 EMUs built by British Rail. These were in turn replaced by spare BR class 313 dual-voltage EMUs, then around 2009 by new Bombardier class 387 EMUs, then in 2019 by new Bombardier class 710 EMUs.

P.C.Hagger was born in West Hampstead on 1873-05-15, the illegitimate son of Ellen Hagger. His birth was registered as "Joseph Corr Preston"; apparently the Hagger family used the surnames Hagger and Preston interchangably. He married Emily Elizabeth Baker (born 1883) at Ampthill in 1909 and their daughter Olive was born the following year in Croxley Green. At this point he was using the name "Joseph Corrie C P Hagger". (My thanks to Peter Hagger and Martin Hagger for this information.)

The reason that trains did not use the south side of the triangle is that they were "handed" and so it was important not to let them get the wrong way round as this would prevent them coupling to other trains. See page 91 for an explanation of the 1941 date.

The passimeter is believed to be at Kilburn Park because the photo matches the current interior appearance of the station in various ways.

The story of the baby has appeared in a number of forms. The mother's full name was apparently Mrs Daisy Britannia Kate Hammond while the father was George Hammond. The baby's actual name was Marie Ashfield Eleanor Hammmond; she married George Henry Cordery in 1947 and died in Hillingdon in 2005. Both "T.U.B.E." and "Joselyn" ("jostling", because it was rush hour) were newspaper suggestions or fabrications.

According to the Uxbridge & West Drayton Gazette, Mrs Hammond was already on a Bakerloo train when she went into labour at Marylebone. The train was cleared of passengers and then ran non-stop to the sidings beyond Elephant & Castle, where a Dr Gulley - waiting with an ambulance - delivered the baby and then accompanied mother and daughter to Lambeth Infirmary. On the other hand, the Belfast Telegraph claims that Mrs Hammond was taken ill as the train approached Elephant & Castle, where typists on their way home formed themselves into a screen on the platform whilst porters ran for a doctor. (While I prefer the first version, I would have thought London Road depot would be a better place to send the train.)

A journalist from the Daily Express suggested to Lord Ashfield that he become the baby's godfather. His full response was "I should be delighted, if the baby's parents are willing. Of course it would not do to encourage this sort of thing, as I am a busy man, but as this is so far as I know an event which is without precedent in the history of the Bakerloo, I think we ought to mark the occasion." The christening, which he of course attended, was at Wealdstone.

It's unclear if any babies were born to women sheltering at night in tube stations during World War II (see page 90). On the one hand, the sheer numbers involved make it likely that it happened, but on the other hand the conditions in the stations would not have been good for someone heavily pregnant and one would expect them to shelter elsewhere. Jerry Springer, the US television presenter, politician, actor (and much else) was born on 1944-02-13; he claims it was on the platform at Highgate station while it was being used as a shelter, though I have been unable to find any independent corroboration.

London Electric Railways produced a perspective diagram of the new station. Much as I would have liked to include it in the book, copyright reasons prevented me.

Apparently a scale model of the station, showing all the various underground tunnels, was donated to the LT museum in 1987. I have no idea whether it is still there.

A report in July 1937, based on an earlier suggestion by the Southern Railway (SR), proposed extending the Bakerloo to a station at Camberwell Green, after which it would surface and take over the SR line from Peckham Rye to Barnehurst via Eltham. It also considered taking over the branch from Nunhead to Crystal Palace (High Level), which actually closed on 1954-09-20. The obvious destination for the main route was not Barnehurst but Dartford, but this would mean extending beyond the 12-mile limit of the London Passenger Transport Board's authority. One solution to this would be for the SR to run a shuttle between the two stations, but the report also proposed terminating most trains at Barnehurst while others would continue to Dartford. A new depot would be required - a site on SR land at Kidbrook or Slade Green was considered. The proposal was only just financially viable and was never progressed.

There is a photo of a train carrying the blue stripe on page 123 of the book.

The term "adjust" is a bit of an understatement: in one map they published, Uxbridge was shown due north of Latimer Road (when it is actually 18.2 km or 11.3 miles further west), Aylesbury due north of Turnham Green (39.6 km or 24.6 miles further west), and Wotton (on the Brill branch) due north of Richmond (48.7 km or 30.3 miles further west).

The exact percentages in the pooling scheme were:

| Company | Original scheme | Revised scheme |

|---|---|---|

| LPTB | 62.00473 | 62.10364 |

| Southern Railway | 25.55158 | 25.48506 |

| LNER | 6.01488 | 5.99922 |

| LMSR | 5.09340 | 5.08014 |

| GWR | 1.33541 | 1.33194 |

At the time the picture was taken the lines were paired by direction, not by use; see the diagrams on page 80. The train is on the northbound fast line heading towards the camera.

The references to Milton Keynes and Oxford are explained in detail on my Metropolitan Line page. In 1892 the Metropolitan was connected to the Aylesbury & Buckingham Railway, which it had purchased; the far end of that line was at Verney Junction, 15 km (9 miles) from central Milton Keynes and 11 km (6½ miles) from the nearest part of the town. In 1899 it took over operation (but not ownership) of the Wotton Tramway, the far end of which was at Brill, 17 km (11 miles) from central Oxford and 12 km (7 miles) from the nearest suburb.

To clarify, the first of the three Metropolitan stations (heading north) was called St.John's Wood Road when it opened on 1868-04-13, was renamed as St.John's Wood (hence "namesake") on 1925-04-01, then renamed again as Lord's on 1939-06-11 in anticipation of the new station opening.

One of the bridges at Kilburn (taken by the author).

The scissors crossover at Piccadilly Circus has since been reverted to a simple trailing crossover.

The sleet locomotives were consructed from 1903 Stock from the Central Line. The driving cab and front bogie was cut off two motored cars, a new body was constructed to join them, and two (one in the prototype) de-icing bogies were fitted to the body. These carried three ice cutters (rotating heads with ridged steel rollers to break up the ice) between two brushes each, two on the sides for the positive rail and one in the middle for the negative.

The deferral was announced on 29th September.

A proposed signalling diagram from the early 1950s shows the mid-points of Elephant & Castle and Camberwell Green stations as 2556.2 metres (8386.5 feet) apart. The latter would have three platforms; a diveunder track allowed arriving trains to reach the westernmost platform, meaning five of the six possible combinations of simultaneous arrival and departure were possible instead of the three obtainable with a flat layout. Three sidings extend to Love Walk, a distance of 427.3 metres (1402 feet), giving room to store four 7-car trains. No signalling provision is shown for the intermediate station, which other documents say would be called "Camberwell Gate" with the entrance at the junction of Walworth Road, Camberwell Road, and Westmoreland Road.

The earlier speed control system was installed in 1935 on Kilburn Park escalator 3, Maida Vale escalator 1, and Warwick Avenue escalator 1. Speed control came back into use - in both directions of use - in 2021, on the escalators at Battersea Power Station and Nine Elms on the Northern Line.

The strangest proposal to extend the Bakerloo Line was made by the Liberal Party (now the Liberal Democrats) in March 1967. For once this didn't involve Camberwell. Rather, after crossing the Thames, the Bakerloo would be diverted into new platforms at Waterloo facing eastwards rather than southwards. It would then curve northwards to intercept the Waterloo & City Line just south of the river, taking it over as far as Bank. Rather than ending there, the station at Bank would be rebuilt in a V-shape as the start of a large clockwise loop. The first stop on the loop would be a new station between Moorgate and Liverpool Street (rather like the present Elizabeth Line platforms) with "travelators" (sic) connecting it to both. The other stop on the loop would be at Fenchurch Street, northwest of the main line station. The rebuilt Bank station would also have new travelators to Cannon Street main line station (Bank actually gained an entrance opposite there in 2023).

Of course, this leaves the question of what to do with the bit of the Bakerloo between Waterloo and Elephant. The answer was to extend the line from the existing platforms northwards to meet the Piccadilly Line branch from Aldwych to Holborn (the layout at Holborn meant it would be the other terminus, with only five stations in total on the line). And what about the Waterloo & City platforms at Waterloo? They weren't forgotten either. Since the western third of the line would now be sitting spare, why not extend it eastwards and then curve north to meet the Northern Line immediately south of London Bridge station?

For completeness, the proposal also included two new main-line size tunnels connecting existing railways (rather like the Elizabeth Line), one from Paddington to Bricklayers Arms and the other from Moorgate to Pimlico (this would use the existing tunnels from Finsbury Park to Moorgate at one end and continue on a road-rail bridge over the Thames to Vauxhall at the other). What is now Thameslink from West Hampstead to Loughborough Junction would also be brought into use as a third main-line connection. The two new lines crossed at a new station between Leicester Square and Trafalgar Square, with travelators to both and to what was then Strand station on the Northern Line. The first line would have a new station between Bond Street and Oxford Circus (connecting to both) plus platforms at Waterloo. The other would have three other stations: between Ludgate Hill (now City Thameslink) and St.Paul's - with travelators to both - at Aldwych, and at St.James's Park (with travelators to nearby government offices). The existing main-line station at Charing Cross would be closed.

Despite claims that it would be more economical - it required only 12 miles of tunnel, rather than the 21 of the government's own plans at the time - and provided wider benefits, nothing came of this proposal either.

Signal KB2 was the last one in the southbound direction controlled by Kilburn High Road signal box. The white hexagon is a standard symbol that indicates that the line is track-circuited and so drivers don't need to contact the signal box just because they are stopped at a red signal. The "T" indicates a telephone.

The building visible just above the front car of the train is the signal box that controlled the crossing. It was only open "as required", so saw very little use. The crossover move was unsignalled, so the points had to be padlocked in position before the train could cross over with passengers on board. In addition, some empty trains were run over the crossover beforehand to ensure that the current rails were clean rather than rusty.

Stonebridge Park depot is about 25,000 square metres and can handle 119 cars, making 210 square metres per car, well in excess of Follenfant's rule (see notes for page 43).

The position of the Jubilee Line platforms was determined by the location of the new ticket hall on Waterloo Road and the escalator links from there to the centre of the platforms. Putting the platforms nearer the Bakerloo and Northern Lines would have required long connections between the platforms and the new ticket hall.

The range £170 to £410 million comes from a National Audit Office report on the Metronet failure. Put simply, the NAO estimated that an efficiently-run Metronet should have spent between £4,690 and £4,870 million of public money but actually spent between £5,040 and £5,100 million. Of the 14 Bakerloo stations managed by Metronet, the report shows:

| Works completed on time | none |

| Works completed over a year late | Maida Vale |

| Works completed up to a year late | Elephant & Castle Piccadilly Circus Regent's Park |

| Works deferred or cancelled | Edgware Road Kilburn Park Lambeth North Marylebone Paddington Warwick Avenue |

| Works still in programme |

Baker Street Embankment Oxford Circus Trafalgar Square / Charing Cross |

The 14 stations outside the Circle Line were Aldgate East, Angel, Earl's Court, Edgware Road (Bakerloo), Euston, Marylebone, Old Street, and Pimlico north of the river, and Borough, Elephant, Lambeth North, London Bridge, Vauxhall, and Waterloo south of the river. The 17 stations in both zones were Aldwych, Covent Garden, Embankment, Euston Square, Euston, Goodge Street, Holborn, King's Cross St.Pancras, Lambeth North, Leicester Square, Russell Square, Temple, Tottenham Court Road, Trafalgar Square, Warren Street, Waterloo, and Westminster.

Signal HR1 is the last one in this direction controlled by Harrow No.2 signal box.

Weekly capping isn't impossible on Oyster-like systems. For example, the Opal card used in Sydney and nearby parts of New South Wales has both daily and weekly capping as well as arrangements like discounts for multiple journeys in the same fare band. The limitations tend to be the number of separate pieces of information that can be stored on the card.

With the abolition of guards (see page 112), repeater signals like the one shown have mostly - if not completely - been abolished.

The first trains to lose guards were the Hainault to Woodford section of the Central Line, in April 1964, while the Victoria Line opened in 1967 without them. The last train with a guard ran on the Northern Line on 27th January 2000.

While I have not been able to obtain numbering details for the 1906 Stock, it appears likely that on the Bakerloo the motor cars were 1 to 36, the trailers 201 to 236, and the control trailers 401 to 436 (it appears that each of the three lines had its own numbering system). It also became common practice early on to use odd numbers for sets that faced one way and even numbers for sets that face the other; it would not be surprising if this applied to the 1906 Stock.

For the 1914 Stock, the two motor cars from Leeds Forge were numbered 38 and 39, the ten Brush motor cars were 40 to 49, and the two trailers were 238 and 239 - it's unclear why 37 was omitted from each series. The ten Piccadilly trailer cars were probably renumbered as 240 to 249.

One of the two 1914 Stock trailers was purchased privately and sent to the Isle of Wight.

The 22 borrowed motor cars were Central London Railway numbers 269-271, 273-290, and 292; the Bakerloo renumbered the first three as 291, 294, and 293 respectively.

The description of the photograph is deduced from the appearance of the visible cars and the track layout at Watford Junction at various times.

The Joint Stock carried LNWR numbers ending with a "J". The motor cars were 1J to 36J, the trailers 201J to 224J, and the control trailers 401J to 412J. London Electric Railways owned cars 19J to 21J, 25J, 26J, 28J, 29J, 32J to 36J, 204J to 206J, 214J, 215J, 217J, 222J, 223J, 401J, 403J, 410J, and 412J. Four-car trains were always extended to six cars at the north end, so only 12 of the motor cars faced south; these were 2J, 4J, 7J, 11J, 13J, 16J, 20J, 22J, 25J, 28J, 29J, and 31J.

The Joint Stock cars retained by the LMSR were formed into three sets as follows (note that 401J lost its control equipment in the conversion):

| LNWR numbers | LMSR numbers | |

|---|---|---|

| 1923 system | 1932 system | |

| 32J-401J-31J | 825-640-770 | 28218-29499-28217 |

| 5J-214J-35J | 2394-337-904 | 28213-29497-28216 |

| 12J-213J-16J | 2415-593-2416 | 28214-29498-28215 |

After withdrawal from the Bakerloo Line, the 1920 Stock was planned to be refurbished and then used on the Great Northern & City Line, but this was interruped by World War II. Two of the motor cars were used on the Aldwych shuttle of the Piccadilly Line for a short while and others were used as engineering locomotives. The trains were stored until after the war; 35 cars were then scrapped while the remaining 5 formed a mobile classroom (moved by other locomotives) until being scrapped in 1968.

The numbering changed over the years:

| Type | 1920 | 1926 | 1930 | 1934 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor | 480 to 499 | |||

| Trailer | 800 to 819 | 1316 to 1335 | 7230 to 7249 | |

| Control Trailer | 700 to 719 | 1700 to 1719 | 2043 to 2062 | 5170 to 5189 |

The complete Standard Stock production was:

| Batch | Builder | Motors | Trailers | Control Trailers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 | BRCW | 0 | 35 | 0 |

| CLCo | 41 | 40 | 0 | |

| MCWF | 40 | 0 | 35 | |

| 1924 | BRCW | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| CLCo | 0 | 0 | 25 | |

| MCWF | 52 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1925 | CLCo | 48 | 0 | 0 |

| MCWF | 0 | 5 | 67 | |

| 1926 | MCWF | 64 | 48 | 0 |

| 1927 | MCWF | 110 | 160 | 36 |

| UCC | 77 | 37 | 68 | |

| 1929 | UCC | 18 | 17 | 18 |

| 1930 | MCCW | 22 | 20 | 20 |

| UCC | 2 | 4 | 0 | |

| 1931 | BRCW | 0 | 90 | 0 |

| GRCW | 0 | 40 | 0 | |

| MCCW | 145 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1934 | MCCW | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Totals | 1,460 | 645 | 546 | 269 |

The "58 trailers" were part of the MCWF 1927 build and were originally numbered 7513-7570, but were renumbered as 70513-70570 when converted. Two of these had single doors added at each end as a trial for what was planned as 1960 Stock on the Central Line. These were 70518 (returned to service after modification on 1957-06-27) and 70545 (1958-01-17).

Car 23J was owned by the LNWR, but the entire Joint Stock fleet was managed by the LER.

The Watford Replacement Stock was the 1930 build by MCCW. The original numbering was 161-182 (motors), 1340-1359 (trailers), and 2063-2082 (control trailers). In 1931 there was a mass renumbering that made them 3342-3363, 7250-7269, and 5190-5209.

The location of the lower photograph was deduced by matching the nearby housing and station buildings against Ordnance Survey maps; Wembley Central is the only one that fits.

The photo is taken from the footbridge connecting Northwick Avenue and The Ridgeway. The furthest track connects to the Up Slow just north of the footbridge and fans out into the four sidings of Kenton goods yard; the wagons in the distance are opposite the station platforms. The white post holds a loading gauge, which allows staff to check that the load on any wagons is not too high for the running lines.

The 1928-built Bakerloo Harrow cars were part of the 1927 batch in the table above. The 1928 car numbers were originally 254-267 (motors), 1265-1278 (trailers), and 1960-1973 (control trailers), later renumbered to 3284-3297, 7215-7228, and 5156-5169. The additional 1928 cars were motor 222 (later 3034) and control trailer 2038 (later 5128); the 1929 cars were motor 187 (later 3001), trailers 1314 and 1315 (later 7054 and 7055), and control trailer 1975 (later 5002).

Even after they were rebuilt with flat ends, the 1935 Stock could be identified by the square marker lights at the ends instead of the normal round ones.

On 1974-05-06 the East London Line switched from District Line subsurface stock to 1938 stock. The trains used came from the Bakerloo, where they were surplus to requirements.

The five trains lost because of service reductions went on 1981-11-15, 1982-02-17, 1982-03-02, and 1982-03-16 (two trains). Fifteen trains were replaced by 1959 Stock trains from the Northern Line between December 1982 and June 1983. All twenty were taken out of service. On 25th January 1984 a 16th train was transferred from the Northern Line for the extension back to Harrow & Wealdstone (see page 108). The remaining 16 trains were replaced by further 1959 Stock trains from the Northern Line between August 1984 and November 1985.

The "Starlight Express" train consisted of the cars 11012-12027-012256-10012 + 11291-012371-10291. It was the last of these that advertised "Starlight Express" itself, the other cars advertising other musicals such as "Evita". Cars 10012 and 11012 were the first 1938 stock 'A' and 'D' end Driving Motors to be built.

The exact dates of operation on the Northern Line were 1986-12-15 to 1988-05-19.

On the Isle of Wight car 10291 became 127 and 11291 became 227, forming unit 483 007. The unit spent most of 2020 in long-term ("C4") overhaul. It returned to service on 2020-12-11 but was withdrawn again the following day. It next ran on 2020-12-24, then stayed out of service until 2021-01-03, the closing day of the service. Unit 007 ran until 11:49 when, arriving at Ryde St.John's Road on its return from Ryde Pier Head, it was exchanged for 006. The line reopened on 2021-11-01 (7 months later than planned) with a new fleet of 5 class 484 trains, each built from two former District Line "D78 Stock" cars, in turn built between 1978 and 1981. It is planned for the Isle of Wight Steam Railway to preserve train 483 007 at Havenstreet station, initially as a static display.

More precisely, the first fifteen 1959 Stock trains arrived between December 1982 and June 1983, one on 25th January 1984, and another fifteen between August 1984 and November 1985. Thirteen went back to the Northern Line between May and October 1986 in exchange for fourteen 1972 Stock trains (the four-car part of another one was written off in the Kensal Green collision - see page 145). The remaining eighteen went back between March 1988 and July 1989 in exchange for nineteen more 1972 Stock trains.

When the trains first arrived in 1977, not all drivers had been trained on them. When trains reversed at Elephant & Castle, drivers "stepped back", walking the length of the platform while the train they had brought in was taken out by a different driver while they in turn took out the next train to arrive on that platform. There was therefore concern that an untrained driver might find themselves with a 1972 Stock train that they didn't know how to work. To avoid this, until the training programme was complete, 1972 Stock trains came out of service at Waterloo and reversed in London Road depot.

As well as the 33 trains of 1972 Stock listed above, one arrived from the Northern Line (in two halves) on 10th and 16th September 1992.

A collision at Piccadilly Circus on 1996-12-03 wrecked one driving motor from the 4-car unit of the train involved. The only spare vehicle was an UNDM, the survivor of a collision at Harrow in 1994. Therefore this was combined with the remaining three cars to form a unique DM-T-T-UNDM unit. To put the remaining driving cab at the outside end when the unit was coupled into a complete train, it had to be turned around. To indicate the special formation of this unit, the cars were renumbered from 3357-4357-4257 and 3439 to 3299-4299-4399-3399 respectively.

With the withdrawal of the class 483 trains on the Isle of Wight (see notes on page 128), the 1972 Tube Stock are the oldest trains running in the UK other than on preservation lines. A life-extension project carried out from 2014 to 2019 means these trains should be servicable until 2035 (i.e. more than 60 years). Despite this, the fleet is averaging 10,000 km between failures.

Mark Robert Orsman died on 2021-04-08. As well as his work on the Underground, which included leading the Rolling Stock Safety Task Force following the King's Cross station fire, he was also a director of Chiltern Railways.

The first use of separate lamps rather than a moving plate appears to have been the Marylebone extension. This was probably the first use of separate lamps on any of the London Electric Railway tube lines.

At facing points, where the train could go either way (e.g. approaching Elephant & Castle or the connection to London Road depot) one signal was mounted on each side of the tunnel and applied to that direction, so the driver would either see two red lights, meaning stop, or a red and a green, meaning he could proceed.

The left end of the diagram is to the south/east, with the lines descending into tunnel. Red levers control signals; when pulled forward they mean the signal can clear (provided that the line ahead is clear). Black levers control points; pushed back means the points are in the "normal" (usually straight) postion while pulled forward puts them in the other, "reverse", position. The circles above the points levers illuminate "N" or "R" if the points are locked and detected in the selected position. Lever 9 (blue) is the northbound "king lever"; when pulled forward, the northbound tracks work completely automatically with the signals re-clearing after each train. This can only be used with the points in the appropriate positions. Lever 2 (yellow) is an emergency release. Note that each lever has a catch that has to be pulled to move it. Lever 2 has a "collar" around the main lever that blocks the movement of the catch, preventing it from being operated by accident.

Just visible to the left is an indicator showing the destination of the next approaching northbound train. The six options at this time, from top to bottom, were Watford, Harrow, Stonebridge Park, Stonebridge Park (empty from Queen's Park), Queen's Park, and Special. The plate to the right of the illuminated diagram is another train describer: the small black dots are lamps that light up to show the destination of the first three trains in each direction (each column represents a train, each row a destination).

The levers are:

|

|

|

The photos on pages 60 and 122 show the north shed siding numbers. Sidings 21 and 24 are actually the northbound and southbound through lines.

Though the LNWR generally used traditional "lower-quadrant" signals, where the arm dropped down at an angle to indicate "clear", Queen's Park was fitted with the then new-fangled "upper-quadrant" signals, where the arm raises instead. Even today the UK national railway network has a mixture of the two.

More information about the New Lines signalling, including the original rulebook, can be found on dedicated pages elsewhere on this site.

The signal was originally called "HS2/9" because the two heads would be operated by separate levers in Watford High Street signal box. Watford Junction PSB used push buttons to set routes, one for each signal, so each signal had a single number.

Signal box codes on the Underground normally consist of a line code (e.g. "M" for Metropolitan main line or "B" for Bakerloo) followed by letters which normally run in alphabetical order from one end of the line to the other, though often with gaps. There is a suggestion that every station was allocated a code, even if it didn't have a signal box, but this wouldn't explain the existing Bakerloo allocations. In the 1950 proposals, Camberwell would have been "BT".

The first letters for the various lines were (some have since been withdrawn):

| Bakerloo | B | Queen's Park and southwards |

| Central | C | Bank and westwards |

| L | Liverpool Street and eastwards | |

| Hammersmith & City | O | Aldgate to Hammersmith |

| District | E | Earl's Court to Whitechapel |

| F | East of Whitechapel | |

| W | Earl's Court and westwards | |

| Jubilee | T | Bond Street and eastwards |

| Metropolitan | J | Harrow-on-the-Hill to Amersham, Chesham, and Watford |

| M | Baker Street to Uxbridge | |

| Northern | none | Golders Green and southwards |

| A | Brent Cross to Edgware | |

| N | High Barnet branch and planned extensions | |

| Piccadilly | P | Earl's Court and eastwards |

| W | Baron's Court and westwards | |

| Victoria | V | entire line |

The PM prefix on the fog repeater indicates it was for a signal controlled from Cockfosters (Piccadilly Line) interlocking.

A free working simulation of the current New Lines signalling is available from SimSig under the name "WembleySub". This was developed with the (officially sanctioned) assistance of the real-life signallers, so is as accurate as I could make it.

The control centre opened on 1986-10-25, initially just replacing Stanmore signal box. The remainder of the Jubilee Line followed in five stages, ending on 1987-04-12. The first section of the Metropolitan Line, at Baker Street, was added on 1988-01-25 but the section east of there as far as Liverpool Street was only added between 1998 and 2001. Adding the Bakerloo started with the section from Queen's Park to Warwick Avenue on 1991-01-06, from there to Piccadilly Circus on 1991-06-30, and the rest on 1991-09-08.

The signal is BB25 (see also the list in the notes for page 133). The upper lamp lights green to indicate the southbound line is clear towards Paddington. For a shunting move into the south shed, the white disc with red bar rotates 45 degrees and one of the two lower indicators lights up with the number of the siding the train will be going into. The three small lights at top light up red if the power on the main line is cut off.